OpenBSD on the Framework laptop

While preparing for my first week at Chainguard, the CEO mentioned that I should order my own laptop. As a ~15 person startup, there isn’t an IT department to handle these sorts of things.

In 2022, the default laptop of choice for a software engineer working on cloud infrastructure is the Apple M1 Powerbook. They hit nearly all the checkboxes: a great screen, powerful CPUs, and battery life that is the envy of any laptop in their class. The arm64 based Macs are fantastic: in fact, I’m typing this from my personal M1 MacBook Air. Ever the contrarian, I however felt that:

- Working at a company that embraces a secure-by-default stance should use an operating system that matches philosophically

- Using a non-standard environment ensures that I will need to learn the underlying system internals

- As an open-source contributor, supporting alternative platforms promotes inclusiveness, diversity, and clean architecture.

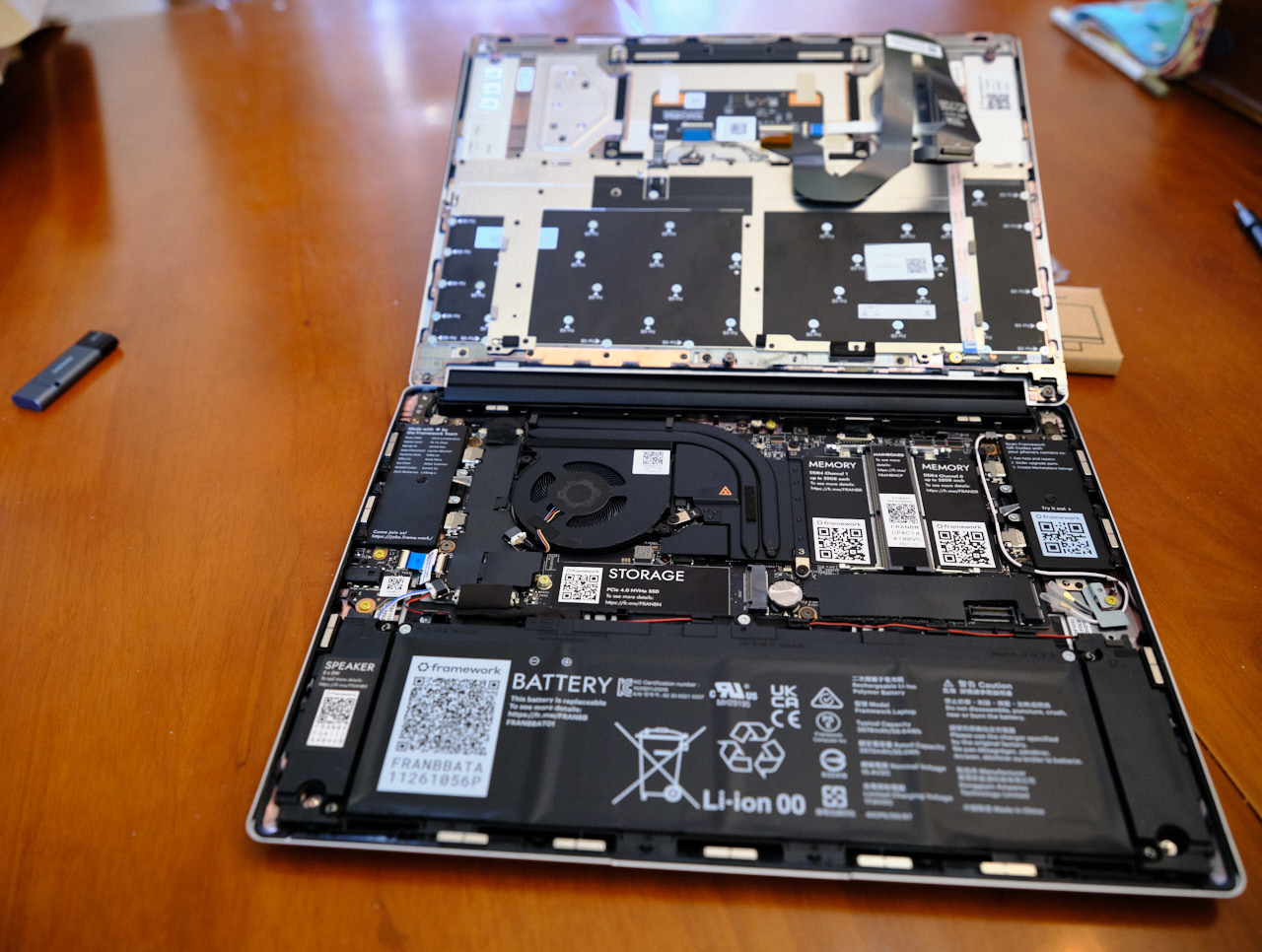

The clear hardware choice for rebellious open-source developers in 2022? The Framework Laptop. It ships with open-source firmware, is available without a closed-source operating system, and is designed to be user upgradeable.

OpenBSD has always been a contumacious alternative, particularly on a laptop. That said, if you work in computer security, you owe it to yourself to try OpenBSD some time: if only to learn the effect a secure-by-default philosophy has on user behavior.

While I expected OpenBSD to be painful on a laptop, I was comforted when I found this another blogger, Joshua Stein, who had detailed their experience (with better photos!)

Assembly

The Framework laptops come in two varieties: a pre-assembled laptop with Windows, and a DIY laptop without an OS. Since I wasn’t planning on running Windows, I opted for the DIY version to save money. I won’t repeat what is already in the excellent Framework Laptop DIY Edition Quick Start Guide, but I’ll share some notes.

Difficulty levels:

- Memory: easy to add

- Storage: easy to add

- Wireless: easy to screw up once

- I/O ports: Trivial (I opted for 3 USB-C ports and 1 USB-A port)

Standout features:

The I/O ports have plenty of clearance from one another. The aesthetics aren’t great, but it means that the ports on each side are always usable, contrary to my MacBook Air.

The case screws are all designed to be half-removed and stay in place. As someone who always loses screws, I really appreciated this.

The magnetic case clasps are also a surprisingly nice reassuring touch

If you make any changes to the RAM configuration, you will be staring at a black screen for the first 1-2 minutes of the next boot. It isn’t reassuring at all.

The webcam functions excellently (except in low-light).

Due to the compatibility issues documented at OpenBSD on the Framework Laptop, I bought the older Intel AX201NGW wireless card for a mere $13 on eBay.

Flashing an OpenBSD USB stick from macOS

I find I learn more about software by installing it from HEAD, or at least a recent snapshot of it. OpenBSD offers nightly snapshot images, so I opted to download OpenBSD from there. I don’t typically do so, but due to my interest in the software signing space, I decided to follow the instructions to confirm that the install image matches the expected SHA256 signature:

curl -O https://cdn.openbsd.org/pub/OpenBSD/snapshots/amd64/SHA256

shasum -c SHA256 --ignore-missing

I had no idea that the shasum command could pull hashes out of a text file like that. This is a great way to avoid corrupt downloads, but doesn’t help at all for avoiding supply-chain attacks, as the checksums and the image share the same mutable distribution mechanism.

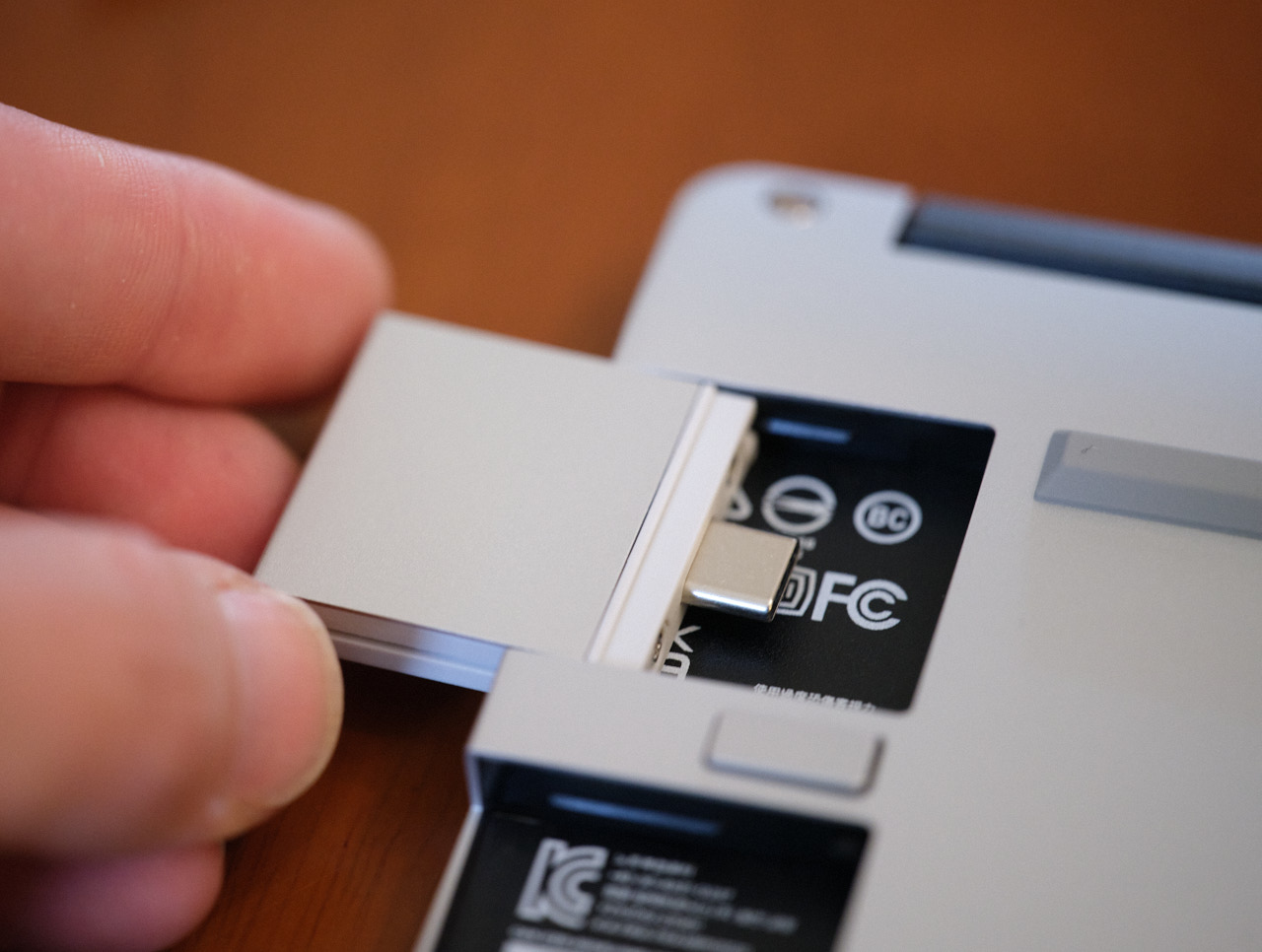

Writing the install image to disk on macOS is the same as with other operating systems. Find the device name for the USB stick:

sudo diskutil list

In this case, it’s a 128GB Samsung Stick connected via USB-C, hiding at

/dev/disk4:

/dev/disk0 (internal):

#: TYPE NAME SIZE IDENTIFIER

0: GUID_partition_scheme 500.3 GB disk0

1: Apple_APFS_ISC 524.3 MB disk0s1

2: Apple_APFS Container disk3 494.4 GB disk0s2

3: Apple_APFS_Recovery 5.4 GB disk0s3

...

/dev/disk4 (external, physical):

#: TYPE NAME SIZE IDENTIFIER

0: FDisk_partition_scheme *128.3 GB disk4

1: DOS_FAT_32 UNTITLED 128.3 GB disk4s1

Unmount the disk, and flash it with OpenBSD:

sudo diskutil unmountDisk /dev/disk4

sudo dd if=install70.img of=/dev/disk4 bs=1m ```

First Boot

During the first boot, I found myself staring at a black screen for a few minutes. It turns out that this weird behavior is expected when booting a standard open-source operating system due to Secure Boot.

Once I rebooted, hit F2, and disabled secure boot, the laptop booted directly to USB.

Welcome to the OpenBSD/amd64 7.9 installation program.

(I)nstall, (U)pgrade, (A)autoinstall, or (S)hell?

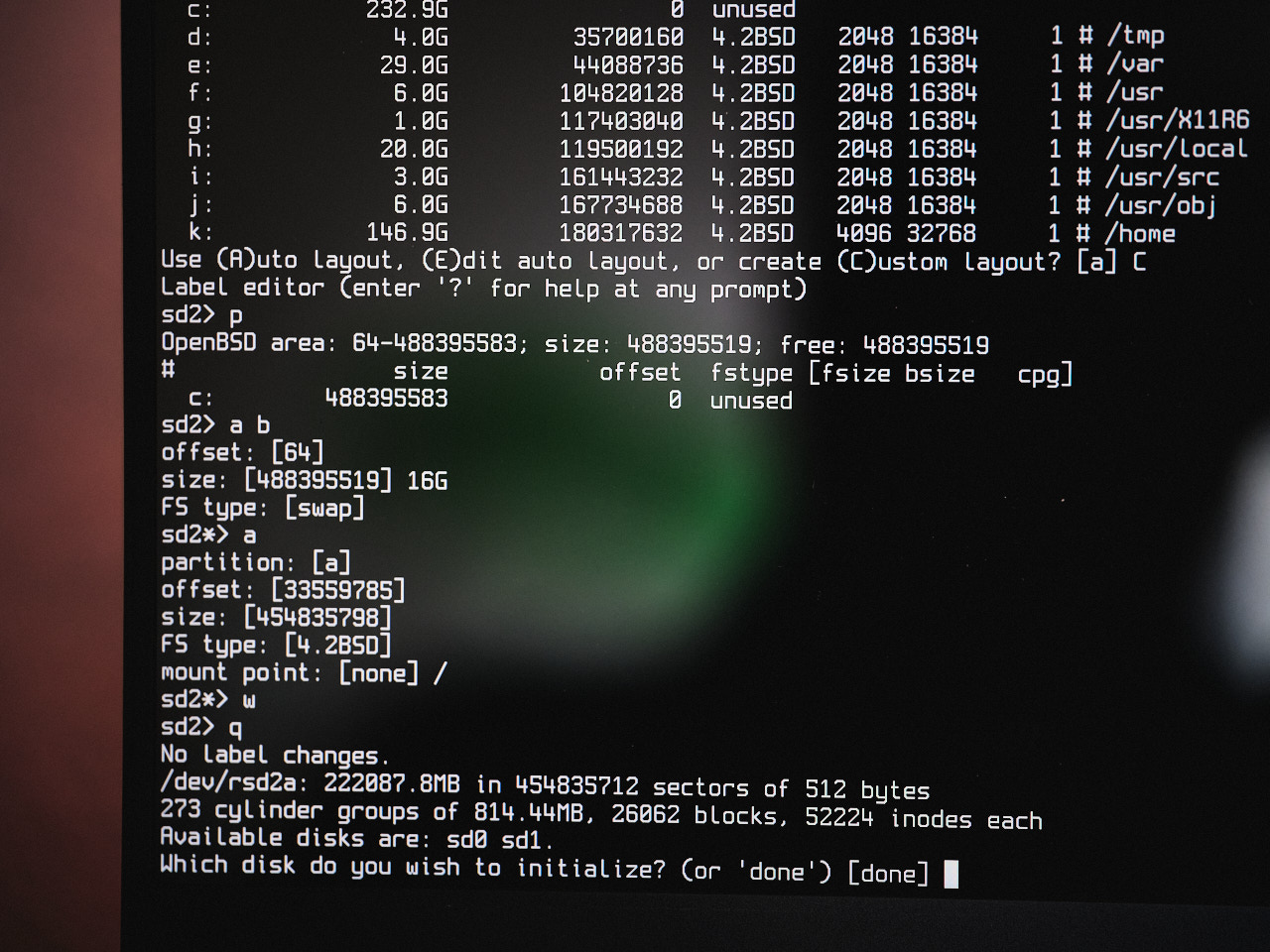

Since this is a corporate laptop, I certainly wanted to use Full Disk Encryption. I followed the OpenBSD Full Disk Encryption, which meant selecting the (S)hell option.

While setting up the disks, the laptop suddenly lost power. What The Fudge? I was pretty sure it was related to my hardware, as I wasn’t fully confident about was the DIMM insertion, so I attempted a RAM dance (something I learned from working in a Google Datacenter over a decade ago), but it happened again.

I then tried reseating all the components, and it happened again. I found a scary sounding forum thread, but it wasn’t a complete match for what I was seeing. The power loss only seemed to happen while I was typing, and only after a couple of minutes.

In my 3rd install attempt, everything worked mysteriously. It was only later that I realized I was battling the same touchpad power event detailed by Joshua Stein. After the installation, I never encountered it again.

One post-installation surprise was that the Intel Wireless card didn’t work - due to a missing firmware blob. I used an older EDIMax USB wireless card, and not only did it work great, but it magically allowed the Intel wireless card to work properly as OpenBSD downloads the necessary drivers during boot time via fw_update: if it has a working internet connection to begin with.

Post-Installation

I floundered about for a bit trying to choose which desktop environment to use, but eventually settled on XFCE. I never did get Gnome to work, but MATE worked properly once I ran:

doas rcctl enable messagebus avahi_daemon

doas rcctl start messagebus avahi_daemon

I was very impressed that nicities such as hot-plugging a new display and my gnubby key worked out of the box. The OpenBSD of 15 years ago wouldn’t have. Since this was a laptop, I enabled power management, though I’m not honestly not sure if it helps at all:

rcctl enable apmd

rcctl set apmd flags -A

rcctl start apmd

Once the machine was installed, I configured doas to allow the users in the wheel group (me) to easily execute commands as root:

echo "permit persist :wheel" > /etc/doas.conf

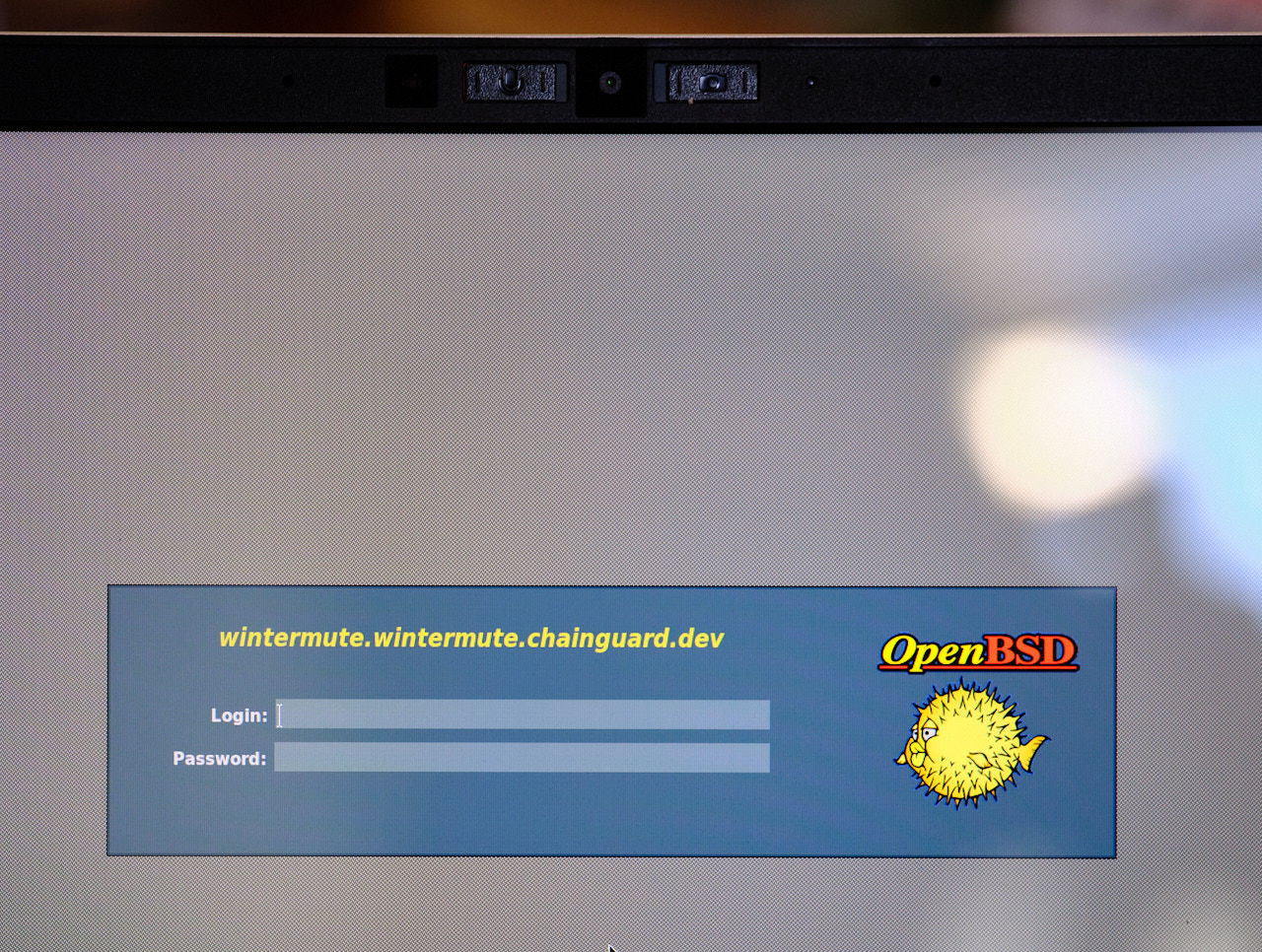

I set the hostname:

echo wintermute.chainguard.dev | sudo tee /etc/myname

sudo hostname $(cat /etc/myname)

I copied the network configuration from the EDIMax USB ethernet to the Intel card I was using:

doas cp /etc/hostname.urtwn0 /etc/hostname.iwx0

OpenBSD disables audio/video recording by default, which makes it difficult to use video-conferencing software. I added these values to /etc/sysctl.conf:

kern.audio.record=1

kern.video.record=1

To allow regular users access to the video device, you’ll need to set ownership – even after every upgrade:

sudo chown $USER /dev/video*

I configured OpenBSD to default to using my USB microphone for input and output. Oddly enough, there doesn’t seem to be an easy way to enumerate audio devices in OpenBSD, so none of the graphical audio switchers work well.

doas rcctl set sndiod flags -f rsnd/0 -F rsnd/1

doas rcctl reload sndiod

I couldn’t get screen sharing to work in Google Meet in either Chrome or Firefox, but eventually made it function in Firefox by disabling the pledge sandbox, as per the mozilla-firefox port docs:

echo disable | doas tee /etc/firefox/pledge.gpu

echo disable | doas tee /etc/firefox/pledge.content

echo disable | doas tee /etc/firefox/pledge.main

echo disable | doas tee /etc/firefox/pledge.rdd

To keep Firefox and other behemoths from suddenly crashing, I joined the staff group and increased the per-process memory limits in /etc/login.conf:

staff:\

:datasize-cur=16G:\

:datasize-max=infinity:\

:maxproc-max=512:\

:maxproc-cur=256:\

:openfiles-cur=4096:\

:openfiles-max=8192:\

:stacksize-cur=32M:\

:ignorenologin:\

:requirehome@:\

:tc=default:

To play music, I installed ncspot, a terminal Spotify player. The Spotify web client requires DRM (Digital Rights Management) extensions, which are not supported on OpenBSD. ncspot requires extended terminal settings to avoid corrupt output: env TERM=xterm-256color LANG=en_US.UTF-8.

Annoyances

The current annoyances with my configuration are:

Fan control: The laptop fan fans seem overactive in OpenBSD, especially given the normal temperature I’ve seen. This is noticeable when watching a video stream.

Chromium / Google Meet: I never did get screen sharing to work, receiving only the following error: “Can’t share your screen: Sorry, an error has occurred when screensharing.” I was able to get it to function in Firefox by disabling pledge.

Zoom: With Firefox, Zoom reports

Zoom is not supported on your operating system, but can be accessed using a User-Agent switcher extension. With Chromium, Zoom starts, but audio input doesn’t work, reportingYour browser doesn't support using computer's Audio device. I haven’t tried a user-agent switcher in Chromium.Editors: While NeoVim is good, I miss VSCode. Perhaps code-server will work with some elbow grease. It requires a newer NodeJS than is available in OpenBSD packages, and my attempt to build an updated resulted in SIGABRT issues.

Cloud Native: Many common cloud-native tools only exist in a Linux-based universe. Don’t expect Docker, Kubernetes, Podman, LIMA, kind, minikube, or ilk to function in OpenBSD. You can still build & push containers using ko and sign containers using cosign.

Resume after Suspend: I don’t know if it’s a thing with encrypted volumes, but I have yet to successfully resume after suspend: The fan spins, I see a login prompt, but am unable to type at it. I haven’t tried very hard to fix this, but it does mean scarier

fscksessions at boot time than I’m used to.

In Closing

I found that most of the heartache in OpenBSD is related to one of two things:

- Using software that isn’t popular with other OpenBSD users: NodeJS, for instance.

- Paranoid security defaults that can be overcome

I plan to continue using it as long as it seems viable.